In Part 3 of our 4-part miniseries on communication in public health, Samantha Cinnick from the Health Resources and Services Administration tells her story of shifting a negative narrative with an important question.

Welcome to Part 3 of our 4-part series on communication in public health. This one is really about the power of questions, good questions, to be transformative. Samantha Cinnick tells the story of working with one group, on an already tough task, when Covid hits. Things could’ve headed in a really negative direction. But she used an important question to open things up, and make sure the focus was on progress.

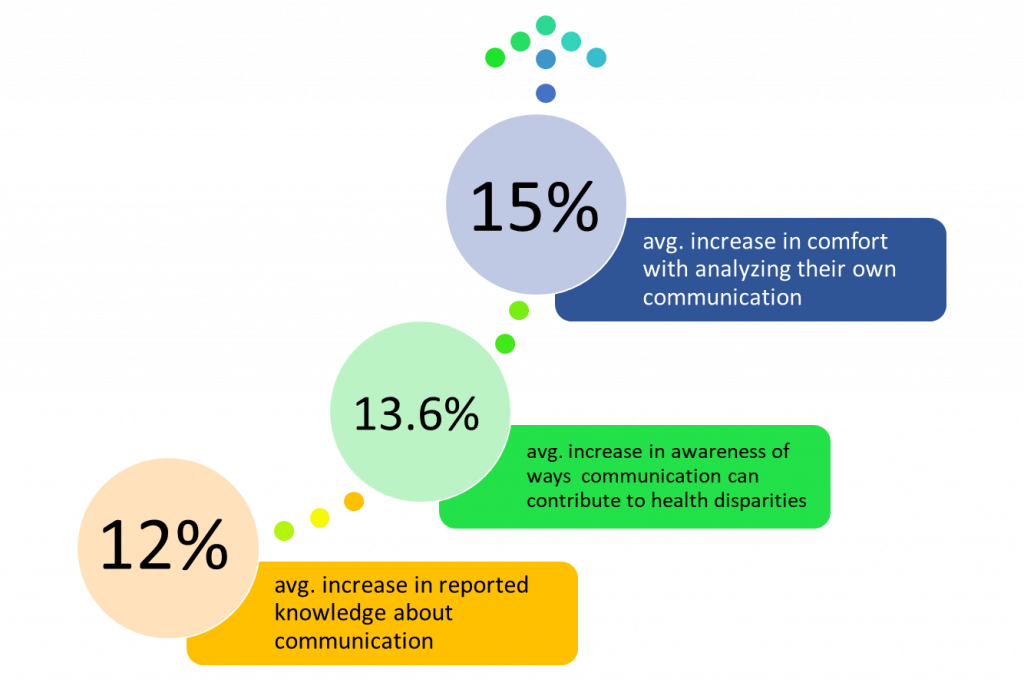

Hi everybody, this is “10 Minutes to Better Patient Communication” from Health Communication Partners. I’m Dr. Anne Marie Liebel. Our Equitable Communication course has been found to make a statistically significant improvement in people’s communication knowledge, confidence, and skills. What this course has, that no other does, is a one hour, live, group meeting for the course participants after the course. So we can get started applying what you’ve learned-in your specific workplace. Learn more at healthcommunicationpartners.com.

Anne Marie: I’m live again via zoom with Samantha Cinnick from the Health Resources and Services Administration. Sam, welcome back to the show!

Samantha: Thanks Anne Marie, happy to be here!

AM: I am so glad that you’ve agreed to do this four-part miniseries with us about communication in public health. And so let’s see, this is our third time sitting down. The first time, we talked about communicating for systems change, and you had some stories there for us. And then last time, you told us about communication that supports collaboration, that supports creativity. So what’s another issue that you are facing that’s related to communication?

Sam: There are so many, right Anne Marie? But the one for today that I wanted to talk about is that often in public health, we are trying to find the root causes of an illness. Of something that’s going on that’s affecting people’s health. And we ask ourselves, what’s the problem? What are we doing wrong? What do we need that we don’t have? We also ask these questions around our organizations, too, and how we’re working with other people. So when you ask these questions–what’s the problem?–you can end up with a lot of lists of negative things about your organization, or about what’s going on.

Ah.

So when you start the process with that line of inquiry, that negative questioning, it can lead to feelings of discouragement for your team. People might be thinking or saying, “I don’t know where to start when I look at this big long negative list.” Or, “I don’t know how to fix it. Why am I even here? What can I contribute?” Especially if the problem seems really big and scary. Especially if they’re not in a formal leadership role where they think they aren’t able to make change. So a communication issue is that, if you want to get people to think in a new way, in a mindset where they are able to make change, what kind of questions do you need to ask? How do you reframe your questioning about the problem so you make it easier to solve, and you motivate your team to solve it? I think in public health for me, that communication problem has been around issues with recruitment and retention in health departments, and often coming at that problem with the deficit-based mindset instead of a strengths-based one.

Communicate for equity

Our course makes a statistically significant difference

Yeah that’s just what I was thinking, when you said deficit-based. This is kind of deficit based thinking, and it’s a big problem. It’s a problem not just in public health, right? I’ve seen the problem in clinical scenarios too. I’ve seen the problem in organizations. So how are you facing this significant issue of our kind of tendency to have this problem focus that leads to a deficit view?

Sure thing! I think a pattern in our podcast series has been that I learned a lot from other people! From mentors, from supervisors. When I was working at the deBeaumont Foundation as a Program Officer for Workforce Development, I was lucky enough to work with staff who had this inquiry framework called appreciative inquiry. They were able to bring in this leadership program that was going to help health departments with their issues around recruitment and retention. And by using that appreciative inquiry framework for asking questions in a way that helps the health departments determine what they were already doing that would allow them to hire and keep employees, we’d be able to change the conversation from “what what’s wrong about the health department?” To “what is right? What should we strengthen? What can be?” And then using that to motivate the employees who are already there, to figure out “how are we going to continue to recruit and retain employees?” It gets people excited, they build capacity as staff members, they want to solve the problem themselves, instead of going outside, or maybe freezing and not being able to solve the problem.

I’m excited about this because, you know Sam, I think we’re talking some similar language here! Because I use a form of inquiry too, with my clients. So I mean we could talk all day about the power of inquiry to do things like you’re talking about, like interrupt deficit perspectives, and show people ways that they can act. It’s so transformative–but it also teaches us a lot about the ways we’ve been doing things, and maybe some new ways that we could do things. So what are you learning from approaching this problem of the root cause exploration with an inquiry mindset? What are you learning from that?

I really like how your how you said Anne Marie that it helps people to see the future, to see what could be. What I’ve learned from using appreciative inquiry, especially with health departments, is that it’s a powerful tool for shifting the narrative, for motivation, and for positive change management. For example, when we were working with these health departments, we didn’t originally start knowing that a pandemic was going to happen!

Aha!

Right? We got a couple months into our leadership program, and Covid hit! So health departments had to deal with one of the most difficult challenges they had ever faced in their entire organization’s history. And these health departments who were engaged in appreciative inquiry, even though they were dealing with Covid testing, and the quarantining, and getting out communications to their communities, they were simultaneously still trying to figure out–using appreciative inquiry–how do we recruit and retain staff?

Wow.

Because there were so many people who were leaving public health at that time, there was an even increased need. And they were able to stay motivated, because they were asking these strengths-based questions about what they were doing. They were looking inside of themselves, even during a public health emergency, and asking themselves: what are we doing really well in this space of recruitment and retention? What can we do to make it even more excellent? And by being able to ask themselves that question, which we very infrequently ask of ourselves–

Right, “what do you do well?”

Yeah, it led to this transformational shift for them. And they were still able to work on recruitment and retention, even during the pandemic.

That sounds like those are some of the learnings that happened with the people that you work with. Did you learn anything about you?

Absolutely! I definitely did. I was definitely inspired by those health departments. But in terms of my own individual learning, I think that what I realized was that–originally, when I started in public health, I thought asking a lot of questions might show that you aren’t a subject matter expert. That you don’t know enough. And that you couldn’t possibly solve a problem. “You’re a beginner! How are you going to solve the problem?” But after working with these health departments, and seeing my mentors and supervisors using these inquiry-based frameworks, I realized that my natural propensity–and others’ natural propensity–to ask questions, is this place where you’re continually learning. And that’s an important communication skill for any leader.

Absolutely. I mean you’ve said so much there too, Sam. Thanks for, thanks for getting personal with us on that! Because the assumptions that you had about what makes a leader were called into question, when you saw these other leaders using these questions. And I think it’s a pretty common assumption that if you’re asking questions, you must be new around here. And like wow, how backwards that is! How really good questions can open things up for people. That’s how we get creative, as you said last time. That’s how we innovate, that’s how we kind of get ourselves out of being stuck in a rut, you know? And I think that’s one of the powers of inquiry, too, is to show how much power even people who are new to a field have, and can be accessed, when we ask good questions. When we put people in the position where they can be knowers, and they can be actors. So what’s the next steps for you? Where do you want to go from here?

I loved your last thought there Anne Marie about how these skills are transferable to anybody whether they’re just starting an early career, or they’re a seasoned professional, right? We’re all leaders in some way.

Yeah.

And so I think next steps for me, I want to help other public health professionals, regardless of where they are in their leadership journey, recognize the appropriate time for expertise which is always needed. And when to lean into that inquiry-like appreciative inquiry–to help solve problems in public health. I know we’ve talked about systems change in the previous episode, and when I think about systems change, that’s not just looking at the wider community or environment. It starts with us! You got to be the change that you want to see. And for myself that includes incorporating much more inquiry into my public health practice. And ultimately what you inquire, becomes reality.

You know I’m going to applaud that. You know I’m going to applaud that Sam, because it does! It’s true! And the power of inquiry to draw people around a problem that they caught, that they care about, and then allowing them to take locally-appropriate, locally-relevant action, because they are invited to do so. Now Sam, before I let you go, in case people want to learn more about appreciative inquiry do you have any resources you can share with us?

I definitely do. They are going to be in the show notes, but there’s a training from the deBeaumont Foundation which provides a little micro learning about the appreciative inquiry cycle

Super

That you can use for your organization. And there’s some links to a book and a website where you can learn more.

Sam thank you so much for coming back on the show, and doing this four-part series with us again, and talking about communication issues in public health. I want to thank Samantha Cinnick from the Health Resources and Services Administration again for being on the show!

Thanks Anne Marie.

It’s been a treat sitting down with Sam, we really are sitting down and talking, just not in the same place. And she’s so brave coming on the show. It’s tough being interviewed. Even though she knows I always ask the same 4 questions, it’s still tough putting yourself and your story out there. She’s not reading a report or some list of statistics, this is her practice she’s talking about, bravely as an early career professional as well. Showing us how much we all have to learn from each other, no matter where we are in the career trajectory. This has been “10 Minutes to Better Patient Communication” from Health Communication Partners. Audio engineering by Joe Liebel. Music by Joe Liebel and Alexis R.